Welcome to the latest issue of The Transportist, especially to our new readers. As always you can follow on Mastodon or RSS.

This month

Transit Funding

WestConnex Speed Limits

The Las Vegas Loop

Posts

Economy of Prestige [Emailed to paid subscribers, now unlocked]

Impermanence, Harborplace and Harbourside [Emailed to paid subscribers, now unlocked]

On Revisiting the USA: Crime, CBDs, and Commuting in the post-Covid era.

An Agent-based Simulation Model for the Growth of the Sydney Trains Network

Research by Others: Tall Cars Bad.

News

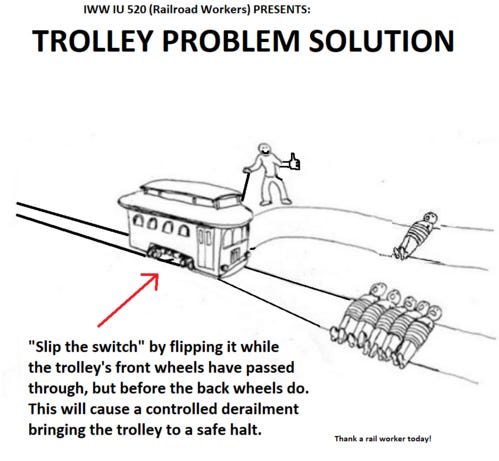

Trolley Problem Solved (we can put philosophy to bed now, it has been up too long)

Transit Funding

Our recent paper about US transit funding: “The overlooked transport project planning process—What happens before selecting the Locally Preferred Alternative?” prompted this really interesting summary by Wendell Cox: The Cost of Opportunity Cost Blindness to Riders and Taxpayers. Our key point was that the rejected alternatives (i.e. BRT) had much better Ridership Cost ratios than the selected alternatives (i.e. LRT). Thus fewer people, person-trips, person-miles, etc. are being served for the same budget than otherwise would have happened.

I would argue that this ineffective use of scarce capital is probably one of the drivers in the weakness of transit use today. US transit has received shares of capital funding far in excess of its market share for decades, with the hope of moving the needle on mode choice. That has not happened.

Elite services (services that decision-makers could imagine themselves using), were built at high costs rather than services that served more people (but not the decision-makers themselves). This is especially important given the positive feedback nature of public transport: the virtuous circle where more services bring about more riders bring about even more services. With the Covid-induced collapse of transit ridership in the US (abetted by the shock and sudden and seemingly permanent switch to much greater work-from-home), this is especially painful, as buses (unlike trains) can more easily be adapted to serve different markets other than the classical suburb-CBD market dominated by rail-based public transport, which suffers the most, since it is office-workers who have spurned transit the most in this shift.

WestConnex Speed Limits

Matt Sullivan in the SMH writes: WestConnex speed limits to rise despite Rozelle interchange fears. My quotes:

However, Sydney University transport professor David Levinson said raising the speed limit by 10km/h [from 80 to 90km (i.e. from about 50 to 56 mph)] was unlikely to worsen congestion near the interchange.

Levinson said raising the speed limit would make it slightly more attractive for motorists to use WestConnex, encouraging more of those reluctant to pay a toll to drive on the motorway instead of surface roads.

He has described the interchange as a “queue jumper” because it allows motorists to get from western Sydney to the Anzac Bridge – the primary bottleneck on the edge of the CBD – faster, displacing others lining up.

More generally:

Assuming they have done a safety analysis that says that the speed limit will not add meaningfully to crash risk, it’s a good idea.

As to whether raising speed limits raises crash risk, normally it would on the road in question, higher speed reduces reaction time and increases the severity of crashes. However it might not increase crash risk on the system as a whole. E.g. the US increased speed limits on rural interstates from 55 MPH to 65 MPH in 1987. Those rural interstates saw an increase in crashes, but other roads saw a decrease, as travellers switched from less safe rural roads to the safer interstates, according to this

To be clear, there is contention about this. And some argument that increasing speed limits on Interstates doesn’t increase crash severity:

Ideally, increasing speed limits will also increase actual speeds (i.e. assuming speeds are restricted by the speed limits rather than congestion (raising the speed limit to 100 km/h doesn’t matter if traffic is congested and the maximum speed is 50 km/h) or drivers willingness to go faster (e.g. raising speed limits from 200 km/h to 250 km/h would not matter if drivers were only willing to go 100 km/h), and the speed limits are abided presently (e.g. raising from 80 to 90 doesn’t matter if traffic is already at 100 km/h because enforcement is weak)). Still, 80 km/h is a pretty low speed limit for a motorway, although a motorway in a tunnel with lots of curves is very different from a straight motorway on the surface.

Obviously any change in speed should be accompanied by a before-and-after safety study on the facility in question, as well as upstream and downstream and parallel routes.

From a demand perspective, increasing speed on WestConnex makes it slightly more attractive for travellers, and should pull some marginal travellers (those on the bubble of whether to pay the toll or not) from surface streets onto WestConnex. Assuming also that WestConnex is safer than surface streets (motorways usually are, due to fewer conflicts and vehicle-vehicle and vehicle-pedestrian interactions), this should reduce crash risk on surface streets.

I am not sure exactly the scope of the speed limit increase, so increasing the speed limit just on the inbound direction in the Inner West but not changing it farther West would not make as much difference (just moving drivers to the bottleneck faster) as increasing it in the West where many drivers are not traveling the whole distance to the ANZAC Bridge and who could take advantage of the higher speeds on trips to other places West of the CBD. It would be more beneficial on the less physically constrained outbound trips

The Las Vegas Loop

Boring tunnels: the Las Vegas Loop

David Levinson, professor of Transport at the University of Sydney’s School of Civil Engineering, says: “Doing this with private vehicles, rather than something that is efficient for the movement of people, like a train, or even a conveyor belt, is an extremely inefficient use of expensive tunnels.”

Levinson is sceptical about the space-saving benefits: “Until the parking garages are also underground, and the network is ubiquitous, it will still need to surface. These portals are not space-free,” he says.

As Levinson points out, governments “generally don’t like people digging up and undermining their cities without strong assurances of benefits,” which perhaps isn’t going to happen until they have seen it done successfully in other locations. Whether or not Musk’s vision for smart subterranean superhighways can scale up and provide a realistic alternative to above-ground roads remains to be seen.

Posts

Economy of Prestige: The Rise of Skyscrapers and the Quest for Status

In urban development, the proliferation of urban skyscrapers transcends mere architectural feats, embodying an ‘Economy of Prestige,’ the corporate version of Veblen’s ‘Conspicuous Consumption.’ Corporate prestige and status rise with the height of their erections. The tallest in a forest of vertical structures is the most conspicuous, and this arms race, the most prestigious. The city with the largest forest of skyscrapers has the highest status. Executives in top level corner offices at those companies overlook others who are vertically challenged.

Impermanence, Harborplace, and Harbour Side

I remember when the Rouse Company’s festival marketplace Harborplace opened in Baltimore in 1980. It was the hotness for a number of years, we probably went monthly when I lived in the Rouse Company’s new planned city of Columbia (founded 1967) and was in high school.

On Revisiting the USA: Crime, CBDs, and Commuting in the post-Covid era.

Some random, but related thoughts … A Report from San Francisco I haven’t spent any real time in the City of San Francisco in years, probably the mid- 2000s. I have of course read the online discourse. I wanted to see for myself. After TRB my son and I visited San Francisco for 3 some days on the way back to Sydney to see some family and friends and show h…

An agent-based simulation model for the growth of the Sydney Trains network

Recently published: Lahoorpoor, B., and Levinson, D. (2024) An agent-based simulation model for the growth of the Sydney Trains network. Environment and Planning B [doi] (Open Access) Agent-based models are computational methods for simulating the actions and reactions of autonomous entities with the ability to capture their effects on a system through i…

Research by Others: Tall Cars Bad.

Tyndall, J. (2024). The effect of front-end vehicle height on pedestrian death risk. Economics of Transportation, 37, 100342.

News

Electric Vehicles

Apple

The Mac is 40 (Computer History Museum event)

The Barcode is 50

AVs

Work from Home

Western Sydney

Aerotropolis development is lagging hopes. Don’t smoke to much Hopium people.

Art