Impermanence, Harborplace, and Harbour Side

I remember when the Rouse Company’s festival marketplace Harborplace opened in Baltimore in 1980. It was the hotness for a number of years, we probably went monthly when I lived in the Rouse Company’s new planned city of Columbia (founded 1967) and was in high school.

It has fallen on hard times, and is to be replaced with this maybe. (See Figures 1,2 below)

That’s what happens if you live long enough, you outlive the full lifecycle of “permanent” buildings.

There are two issues here.

One is that people live too long. If only people had shorter lives, buildings would outlive them.

The other is that the lifespan of buildings is too short. This is the more serious issue.

Many buildings from 100 years ago are still here (I am living in one), and though they are remodelled like Theseus’s Ship, they remain recognisable. Obviously there is a survivorship bias, and many buildings built 100 years ago aren’t still standing, and I do see neighbors tearing down houses to replace with something more modern and fashionable, if less charming and likely with a shorter lifespan than what they replaced.

I wish we were more focused on adaptive reuse and remodeling. The problem appears to be that it is cheaper to start with a blank slate than to retrofit the existing. It feels wrong to waste all that embodied carbon, but who am I to argue with cost structures of the construction industry.

I sense, from observing contractors, that this is because so many workers are so well trained on installing on new construction in an assembly-line-like fashion that remodelling is a time-consuming headache, with uncertainty and dependence on unknown previous contractors (I have yet to see an electrician who didn’t think their predecessors work was crap), and in the Ironies of Automation something they may have forgotten how to do, or at least do well.

So why did Harborplace fail? At least more than any other US shopping mall or festival marketplace ?

This is at least, in part, a Baltimore problem. The crime rate in Baltimore, like the NFL Ravens, is league leading. But it cannot only be that. Harborplace’s younger sister (see Figures 3,4, 5 below) in Sydney, Harbour Side was also recently demolished, along with the monorail that served it. When I got here, Harbour Side was well past its prime, so though I have been inside, it wasn’t very interesting, and certainly not, at that time, of the quality of Baltimore’s original. It was darker, and mostly restaurants and schlock (in other words, needless duplicating Paddy’s Markets), rather than fresh foods and higher end specialties.

It is also a shopping problem, and many shopping malls were decimated by the rise of online shopping, accelerated during COVID. But not all malls were, and shopping in Sydney seems fine. And surely a Harborplace properly managed should be able to retain its market and expand share in a declining sector.

Will a new building change anything that could not have been changed otherwise? Certainly older buildings need upkeep and maybe that was more expensive on the existing than the new?

Another claim is just consumerist novelty seeking. It has to be torn down and replaced to attract customers who became bored with the old center. This seems implausible to me, given how many older centers retain traffic, surely that’s a product of tenants and maintenance and center programming rather than built form.

Putting on my cynical hat: What both sites do is add density. And maybe that’s the reason they were allowed to fall over in the first place: As a means to justify their replacement. Taking off my cynical hat.

Given their initial controversy of building there in the first place (including the effective privatizing of public space) one could see this as a 40+ year game. Still, I don’t think anyone in the real estate sector can actually plan that long. Even the far-seeing James Rouse expected the planned community of Columbia (100,000 people) to be done and dusted in just 13 years.

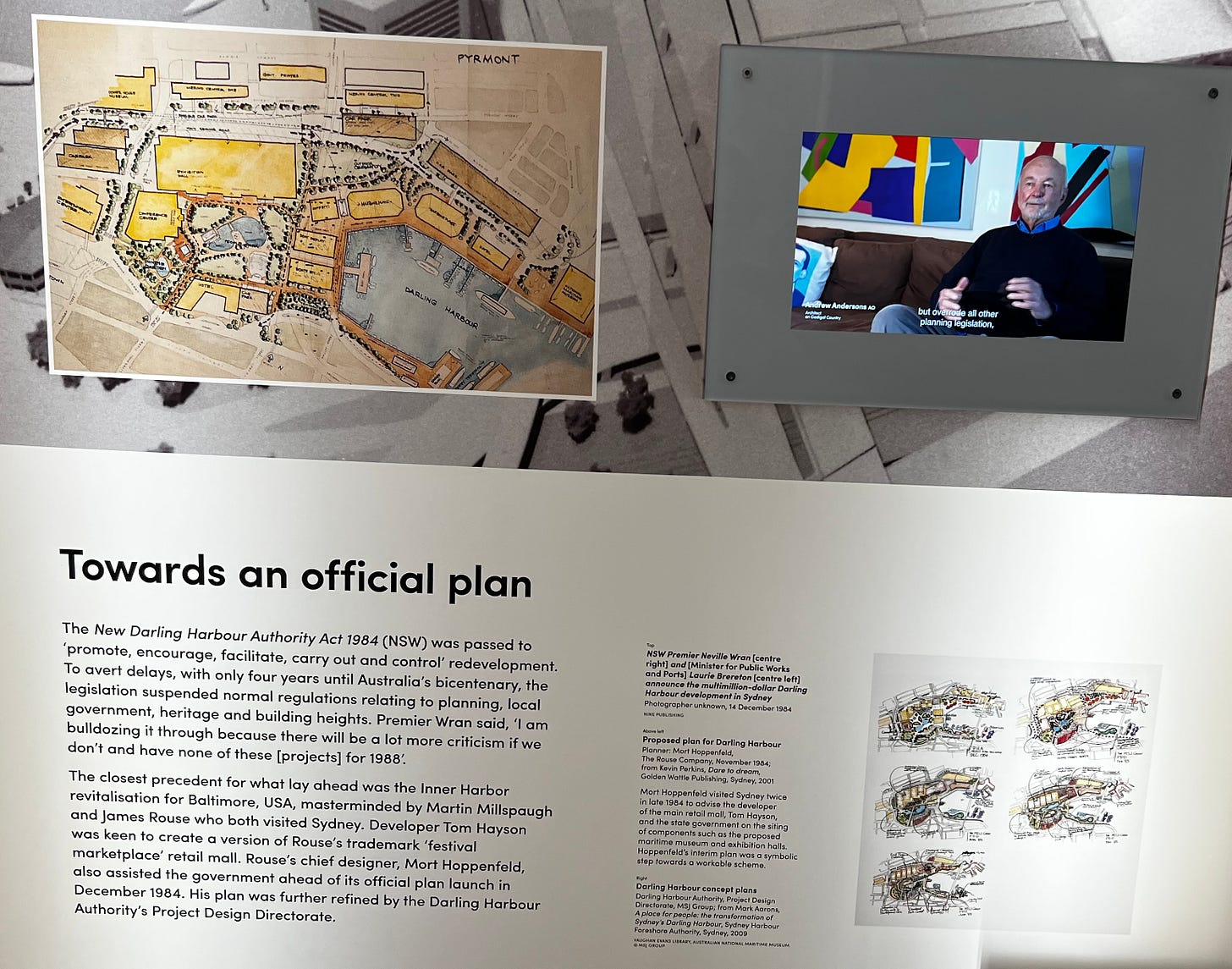

The New Darling Harbour Authority Act 1984 (NSW) was passed to 'promote, encourage, facilitate, carry out and control' redevelopment. To avert delays, with only four years until Australia's bicentenary, the legislation suspended normal regulations relating to planning, local government, heritage and building heights. Premier Wran said, 1 am bulldozing it through because there will be a lot more criticism if we don't and have none of these [projects] for 1988'.

The closest precedent for what lay ahead was the Inner Harbor revitalisation for Baltimore, USA, masterminded by Martin Millspaugh and James Rouse who both visited Sydney. Developer Tom Hayson was keen to create a version of Rouse's trademark 'festival marketplace' retail mall. Rouse's chief designer, Mort Hoppenfeld, also assisted the government ahead of its official plan launch in December 1984. His plan was further refined by the Darling Harbour Authority's Project Design Directorate.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Transportist to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.