Transportist: Lighter Rail

Switching to Mastodon

I have run three polls to date on Twitter about Switching to Mastodon.

October 30 / November 4 / November 30

——————————————————

Done. 6.7% / 7.9% / 26.6%

Will go when others go 14.3% / 29.9% / 24.9%

No 18.1% / 22.8% / 37.9%

What’s Mastodon ? 61.0% / 39.4% / 10.7%

So we are now over 50% of people who responded (N= 105 / 127 / 177) . Ironically, the Twitter sample size has increased as more people say they are leaving, so what’s up with that? (While my personal number of followers has fallen a few percent). I suppose the dumpster fire has attracted onlookers. But as my wife says, there are two types of people, those who run towards the meteorite, and those who run away from the meteorite.

Links

Better Value Transport - Committee for Sydney (I was a peer reviewer)

Emission free modes of public transport - Parliament of New South Wales (I gave evidence)

Follow-Up on Benefit Cost Analysis

Reader Anonymous asks about transport access for the disabled and equity concerns.

Consider the lift. It is essential for people in wheelchairs, but valuable also for people with prams, cars, or bikes, as well as people with difficulty walking. We could try to monetise the value of a new lift at a train station when there is already a staircase. You could ask users how much they would pay for a lift, but it’s unclear how realistic the answers would be given we don’t charge for lifts (This has been tried in buildings — it is unpopular). You can look at the usage of existing lifts, and see how much extra time they require, and how many people still use them, and then use a value of time measure to conclude they are worth at least that much. You could see how many extra users use (or could use - measuring the increased potential) of the station after the installation of the lift. You could see if rents nearby increased after the installation.

There are values of transport-related social exclusion (which affects the disabled as well as people with low incomes, among others), e.g. this paper: Social Exclusion and the Value of Mobility (2011) and this more recent (2022) version by some of the same authors: Place-based disadvantage, social exclusion and the value of mobility attempt to monetise the value of an additional trip. The installation of a lift, for instance, may enable a trip that otherwise could not be taken, or allows a better trip than what would be otherwise made.

But in the end it is a political decision. But it is a political decision that values this at some amount of money. A list of transport disability access projects are funded (they are implicitly more valuable according to political decision-makers than the best unfunded project), and some are unfunded (they are implicitly less valuable according to political decision-makers than the worst funded project).

Reader Jarrett Walker asks about the differences between the US and Australia.

In my view, it’s much more systematic and standardised here in Australia, though they still obsess about travel time savings (TTS) being the primary benefit rather than land value from accessibility. TTS makes more sense for a highway capacity improvement than a public transport investment. Australia still makes decisions before the Business Case is done, especially on the biggest projects where it should matter most, and this mis-alignment of sequence doesn’t bother Australians enough. Treasury still has some say on funding, which is good.

The US treats B/C as a nice-to-have, but not necessary, element to making decisions. It’s a rhetorical device that is heralded if above 1.0, and buried if below 1.0. Transit funding has some standardised evaluation methods from FTA, but they are so hand-wavey as not really mattering.

“The British can calculate the monetary value of the play of sunlight on falling leaves in a perfect autumn breeze.”

My question about B/C is that I don't know how you convert social, environmental, and economic benefit into a common currency without making value judgments on such a massive scale that the whole process might as well be treated as religious. Weighting of inconvertible values is a moral topic unsuited to being concealed inside the false objectivity of B/C.

…

My Canadian clients do something called Multiple Account Evaluation, which quantifies different benefits and disbenefits but pulls back from combining them into an arbitrary or values-laden single index of benefit. That feels more honest.

Identifying winners and losers from different categories (capital costs, variable costs, external costs, fares, user benefits, revenue, etc.) in different groups (taxpayers, users, neighbours, etc.) is important not only for fairness, but also for ability to actually implement the desired project. We have to understand the Political Economy of Access. Success in implementation is determined by who perceives gains and losses and their power. We may then try to figure out whether and how to compensate the losers from the benefits of the project. If we don’t understand that, we won’t get anything done in a democratic system.

However, there are weights or values of all these things because actual priorities are made in spending on X rather than Y. These weights are either said out loud (the lift for the disabled at station S is more valuable than the extra hourly bus run serving group G), or they are hidden under layers upon layers of obscurantism so that any outcome can be achieved and justified depending on the mood and corruption-level of the decision-makers. I prefer transparency, which requires being explicit about how different elements are valued and combined. None of this is perfect, but it can be perfected.

Reader N writes in:

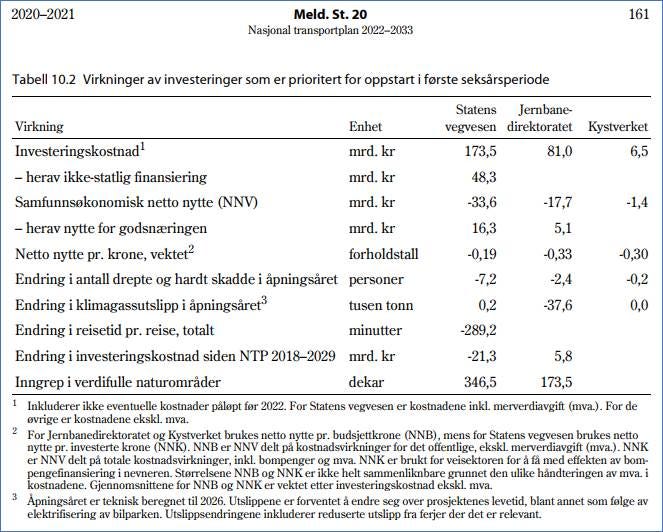

Haha, you should have seen all the wasteful (in cost benefit terms) projects that are being funded in Norway.

National Transport Plan white paper has a table (see screenshot) which summarises prioritized projects during the first NTP period. Although the government has already signaled that there will be cuts relative to this NTP, the mere fact that so many poor projects are being funded is painful.

Statens vegvesen - Norwegian public roads administration

Jernbanedirektoratet = railway directorate

Kystverket = Norwegian Coastal Administration

NNV = net present value. All three are negative!

Netto nytte per krone = Benefit/cost ratio (where cutoff for positive welfare gain is 0 and not 1 due to different formulas). Again, all three are negative.

I believe that the general justification for this goes along the lines of

1) the method does not capture all benefits (like in your post); and

2) Norway places very high emphasis on maintaining rural/remote settlements and usage of the whole country. … There are also a number projects in more central areas that are also being promoted despite negative NPV.

Lighter Rail

Introduction

Light rail costs too much, costs more than expected, it takes too long to build, and it’s intrusive. The Minneapolis Southwest LRT Green Line extension cost estimate has been updated to $US2.75 billion for 14.5 miles (or $US189million/mile, $US117million/km). The Sydney CBD and Southeast LRT is $AU 3B for 12 km, or $AU 250m/km.1 Sydney's line was even more expensive than the very expensive Minneapolis line after adjusting for currency conversion. Reasons include

The very thick depth of concrete poured on the entire line (well beyond what was strictly necessary in the view of most professionals I have talked to),

The cost of relocation of utilities which was borne by the project rather than the utility companies, and many of which may not have needed to be relocated in the first place if a more flexible design strategy and were provided.2

These numbers are big and round, and include different things, and taking them apart so that they are strictly comparable is a challenge. Getting data out of the government of New South Wales is a special challenge. Alon Levy has an excellent Transit Cost Project that documents many of the issues globally in comparing costs. I don’t want to go into those details here. Let’s stipulate it is both a lot of money, and too much money. If transit projects were less expensive, we would have more of them, and as a result more transit access, and as a result more transit patronage and less auto use and fewer negative externalities.

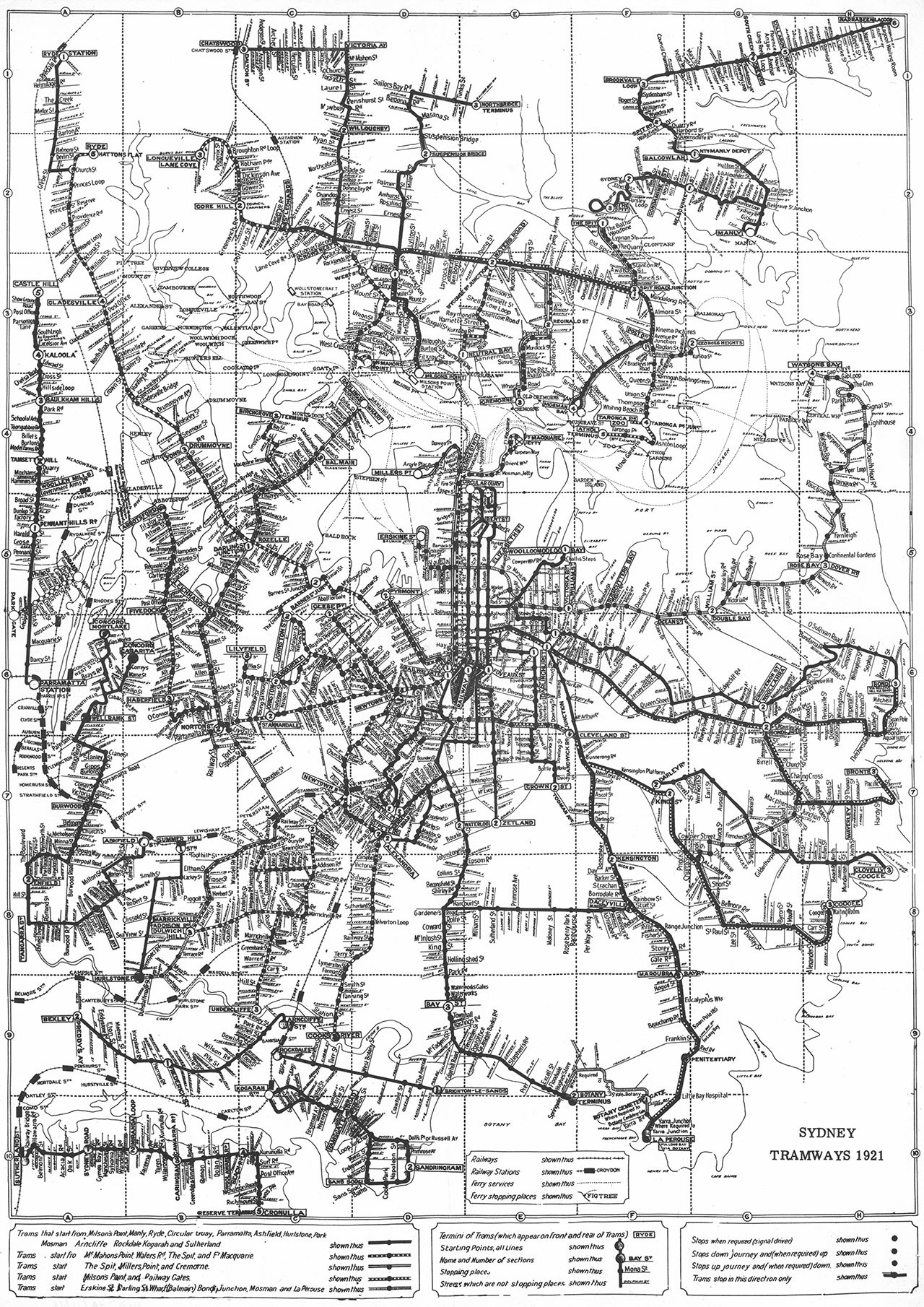

When the first horsecar lines were built in Minneapolis in 1875, the tracks cost $6000/mile.3 Prices were lower of course in the 1800s, so that would be $US163,000/mile (just over $US100,000/km) in 2022 US dollars, still pretty cheap, about 1000-fold less expensive in real terms. It was just some metal track and wooden sleepers and connectors down an already graded dirt road. But it worked, and the technology took off, so that eventually Twin City Rapid Transit became one of the largest streetcar systems in the US. At its peak in 1922, it had nearly 530 miles (850 km) of track and 1021 streetcars, as shown in the map.

Overcoming Overdesign

My general argument is that transport delivery agencies (TfNSW, MetCouncil MnDOT, etc.) are over-designing everything they do, for fear of having only one shot at the apple. The argument is that if you just built it, you won’t be allowed to touch it and improve it for decades. Transport infrastructure is built to “set it and forget it” rather than as an adaptive learning system.

Instead I propose we should build things that are “lighter” not just physically but also metaphorically. Vehicles which are essentially streetcars/trams but have exclusive grade separated right-of-way where they can, but not where it’s too expensive now. Where possible (which is to say almost everywhere if politicians had any backbone) close lanes and streets to cars rather than spend more designing a system for mixed traffic. As the system grows, it would be incrementally upgraded. Can we for instance, build a system with relatively inexpensive older-style trams, with tracks laid in the street rather than embedded in meters of concrete, coupled with inexpensive raised stations4 so there is level boarding?

We could get many of the advantages from rail (including higher ride quality, better navigability, and lower labor costs) without an all-or-nothing approach of build it once and build it forever. Over time, the system would evolve.

With Lighter Rail, We Could Get the Trams Back, and their Riders With Them

For the rest of this post, we will use Sydney as an example. Using the Sydney CBD&SE LRT costs for rebuilding the historic Sydney tram network (at about 291 km peak) would cost 291km* $250m/km=$72,750,000,000 dollars, which seems like a lot of money (more than I have in my pocket at the moment, less than Elon Musk does), but spread over 30 years and 8 million people, even this outrageous costs is only $0.08 per day.5 The recently unnecessarily reconstructed Sydney Football Stadium was $828M. So, at inflated Sydney costs, a new tram network of roughly the same extent as in 1925-1930, would be the equivalent of 88 Stadia. Which would you rather have, a high quality public transport network filtering into neighbourhoods, or 88 football stadia? That choice is easy.

Even with current LRT technologies, with proper planning, management, and oversight, the cost should come down to something reasonable (like 40% the Sydney cost, more similar to the cost in Taipei (Taipei Danhai LRT $US72.6/M or about $AU100/M depending on exchange rates), the total would be $29B, which is only a bit more than the cost of the WestConnex freeway system ($21B apparently, excluding externalities).

With a much lighter technology, such as used back in the day in Sydney and Minneapolis, and more similar to the trams today in Melbourne than to Sydney LRT, this price could be cut significantly further, well within the fiscal capacity of the government and people of Greater Sydney.

Patronage

Now of course no model can accurately tell us the patronage on a Sydney tram system, conditions would be too different from today. But we can try to scope it out.

As a point of reference, Sydney once had many more tram patrons than Melbourne. At their 1926 peak (i.e. excluding World War II and its aftermath), Sydney trams had about 347 million passengers per year, Melbourne 228 million (See Alex Wardrop’s book A Tale of Two Systems).

As of pre-COVID 2019, Melbourne had about 200 million tram passengers per year and buses another 123 million. For the same year, Sydney light rail (the L1 line almost entirely) had 12 million and Sydney buses had about 308 million passengers. Sydney trains (403 million) are better used than Melbourne’s (244 million). If Sydney could acquire today’s Melbourne’s tram ridership without losing bus or train patronage (i.e. the systems were perfectly complementary) Sydney would gain 188 million annual transit users in today’s numbers. (Obviously the bus networks would be reconfigured to be more complementary, and lots of other changes would need to occur.) Given Sydney is a better transit city than Melbourne (higher real population densities, more difficult driving conditions, better rail network) this is not unreasonable.

That might seem too high, so let’s look at it another way. Comparing access, adding Sydney’s 1925 trams to the 2020 transit network would increase the 30-minute person weighted access by public transport by about a third (and 45-minute access by about a quarter). If ridership were proportional to access (which is roughly true, for similarly transit-oriented cities, New York and Boston have elasticities of about 0.9), Sydney public transport could go from 750 million annual passengers to between 900 million to 1 billion annual passengers (2019 levels), consistent with the Melbourne levels. That is a potential level of increase worth planning for. That additional level of ridership would likely justify a plausible expenditure of the magnitude required to achieve it.6

Land Value Uplift

Another way of looking at this is through land value. Analysis of data associated with Manhattan’s Second Avenue Subway showed that land value increased 2-3% with every 100,000 increase in 30 minute person-weighted access (PWA) to jobs.7 We know that the PWA from adding trams to today’s network increases PWA to jobs of 71,000. To get a sense of how much value this would be in the Sydney case, the area under study contained 375,000 dwellings (2016). So (2% uplift)*(71,000 jobs/100,000 jobs)*375,000 dwellings*$1,000,000/dwelling=$AU 5,325,000,000. This is an absolute floor.

This excludes benefits in the region outside the bounding box of the study (shown in the paper)8 (which included some of the original tram lines). This also does not include commercial properties. It is back of the envelope to get the scale and scope. Again, it is well within magnitude for further more detailed consideration of whether the capital costs of the tram restoration project could be paid for with land value uplift.

Net Costs

Today Sydney has about 25km of LRT. Building another 266km at $AU5.325B would require getting costs down to about $AU20M/km. (You can scale with expected value). This is feasible if we don’t over-design the system. Studies as recent as 2017 pegged the initial cost of an LRT on Parramatta Road at $AU15.3M/km, (a bargain), though for a variety of reasons, actual costs have massively overrun initial costs on almost every other project. For more details on cost comparisons in Australasia, see Douglas (2019).9

In any case, I believe that despite experience, with good value engineering, proper scoping and the right actors, and a small bit of luck, achieving that cost is within the realm of the possible. The problem is motivating the actors to favour lower costs when their incentives all lean towards higher costs.

Lighter Rail or Bus Rapid Transit

If you have read this far, you are devoted. You may say, “But David, didn’t you just support a comprehensive BRT network.” [Sydney FAST 2030]. Yes, the BRT can be done next week with political will. Lighter Rail will take several decades to deploy. Several LRT lines were identified in that map that should be prioritised (by 2030). Depending on the outcome of those, more routes should be built. If we can do those first lines cost-effectively, we are more likely to be able to do more of the remaining lines.

And of course before all of that, we should be deploying a comprehensive network of protected bike lanes (PBL) throughout the metropolitan area, taking space from on-street parking. All it takes is will, PBLs and Bus Lanes are pretty close to free. It would be good to see more ambition on the table when talking about transport infrastructure.

As expensive as modern LRT is, it is less expensive than an underground Metro to build, and is easier for users to access/egress when it runs at grade.

It is worth nothing that if other streets, and not just George Street, had LRT, then closing one line for utility service would be less impactful. Even now, other streets have buses, and the George Street line parallels a Sydney Trains route, so can be shut as necessary. See for instance the “Open for Lunch” promotion, on George Street, closing the trams.

Lowry, Goodrich (1979) Streetcar Man. Lerner Publications, Minneapolis, p. 43

Though more expensive than the non-stations that older-style trams had.

Benefits would exceed costs.

Lahoorpoor, B. and Levinson, D. (2022) In Search of Lost Trams: Comparing 1925 and 2020 Transit Isochrones in Sydney. Findings, March. [doi]

Douglas, Neil (2019) Australian Light Rail and Lessons for New Zealand Australasian Transport Research Forum 2019 Proceedings 30 September – 2 October, Canberra, Australia Publication website: http://www.atrf.info

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Transportist to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.