Transportist: "'Why Me?' But Then I Think, 'Who Else'" (1973)

An article from THE SUN MAGAZINE, OCTOBER 7, 1973, about my sister, Sue Beth, who is “profoundly autistic”. Some additional comments in [brackets], hyperlinks added.

“ ‘WHY ME?’ BUT THEN I THINK, ‘WHO ELSE?’”

Story by PATRICIA K. GRANT

Photos by WILLIAM L. KLENDER

SOMETIMES I say to myself, ‘Why me?' But then I think, 'Who else?'

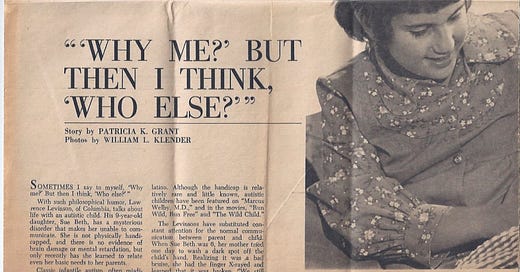

With such philosophical humor, Lawrence Levinson [1941-2020], of Columbia, [Maryland] talks about life with an autistic child. His 9-year-old daughter, Sue Beth, has a mysterious disorder that makes her unable to communicate. She is not physically handicapped, and there is no evidence of brain damage or mental retardation, but only recently has she learned to relate even her basic needs to her parents.

Classic infantile autism, often misdiagnosed and thought to include a dozen or more separate disorders, affects between 2 and 4 persons per 10.000 population. Although the handicap is relatively rare and little known, autistic children have been featured on "Marcus Welby, M.D.,” and in the movies, ‘‘Run Wild, Run Free” and 'The Wild Child.”

The Levinsons have substituted constant attention for the normal communication between parent and child.

When Sue Beth was 6, her mother tried one day to wash a dark spot off the child’s hand. Realizing it was a bad bruise, she had the finger X-rayed and learned that it was broken. “We still don’t know how she broke it, or when it happened,” recalls Roslyn Levinson, a reserved, soft-spoken woman, whose understanding of mental health problems has threatened the superiority of more than one professional.

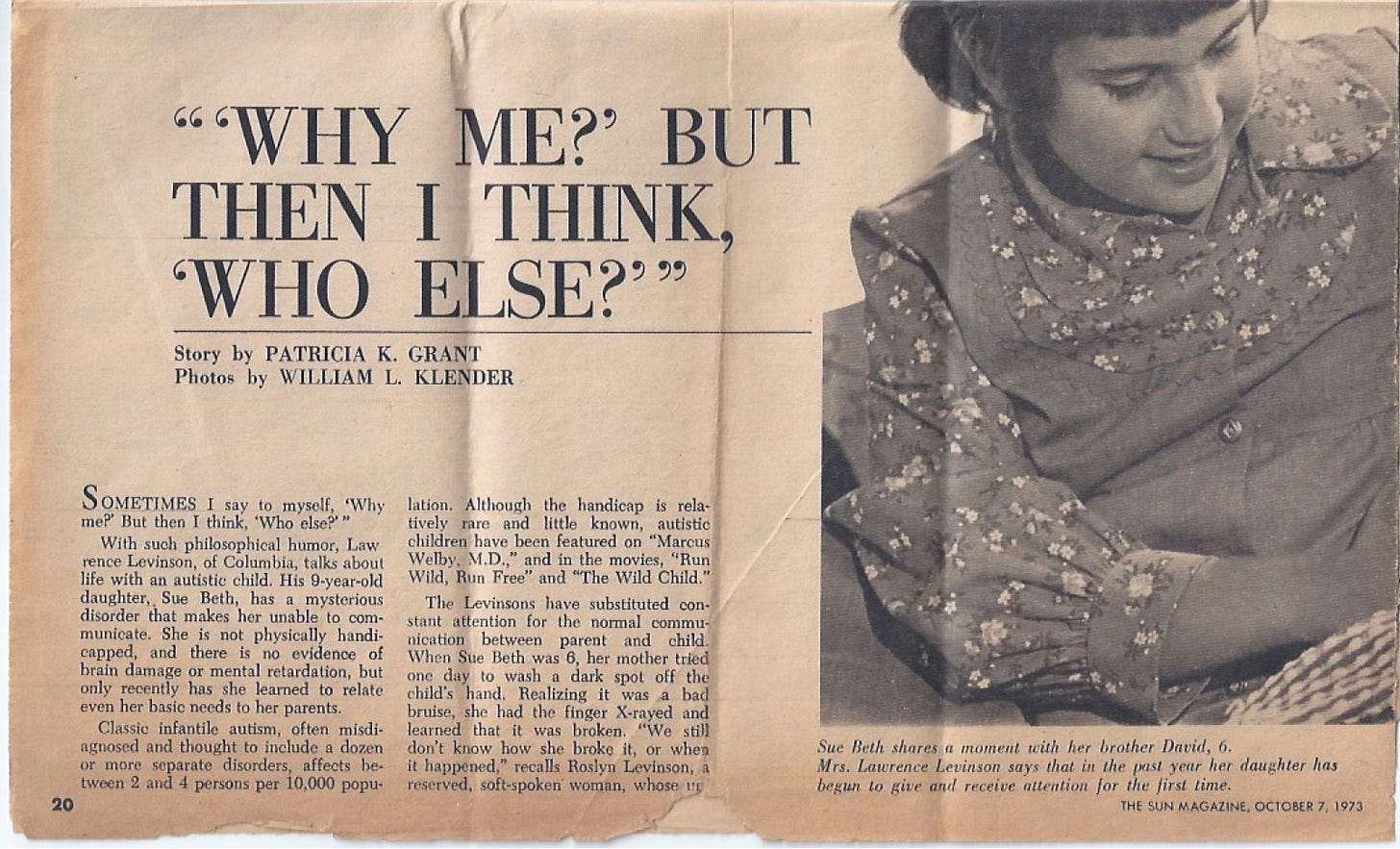

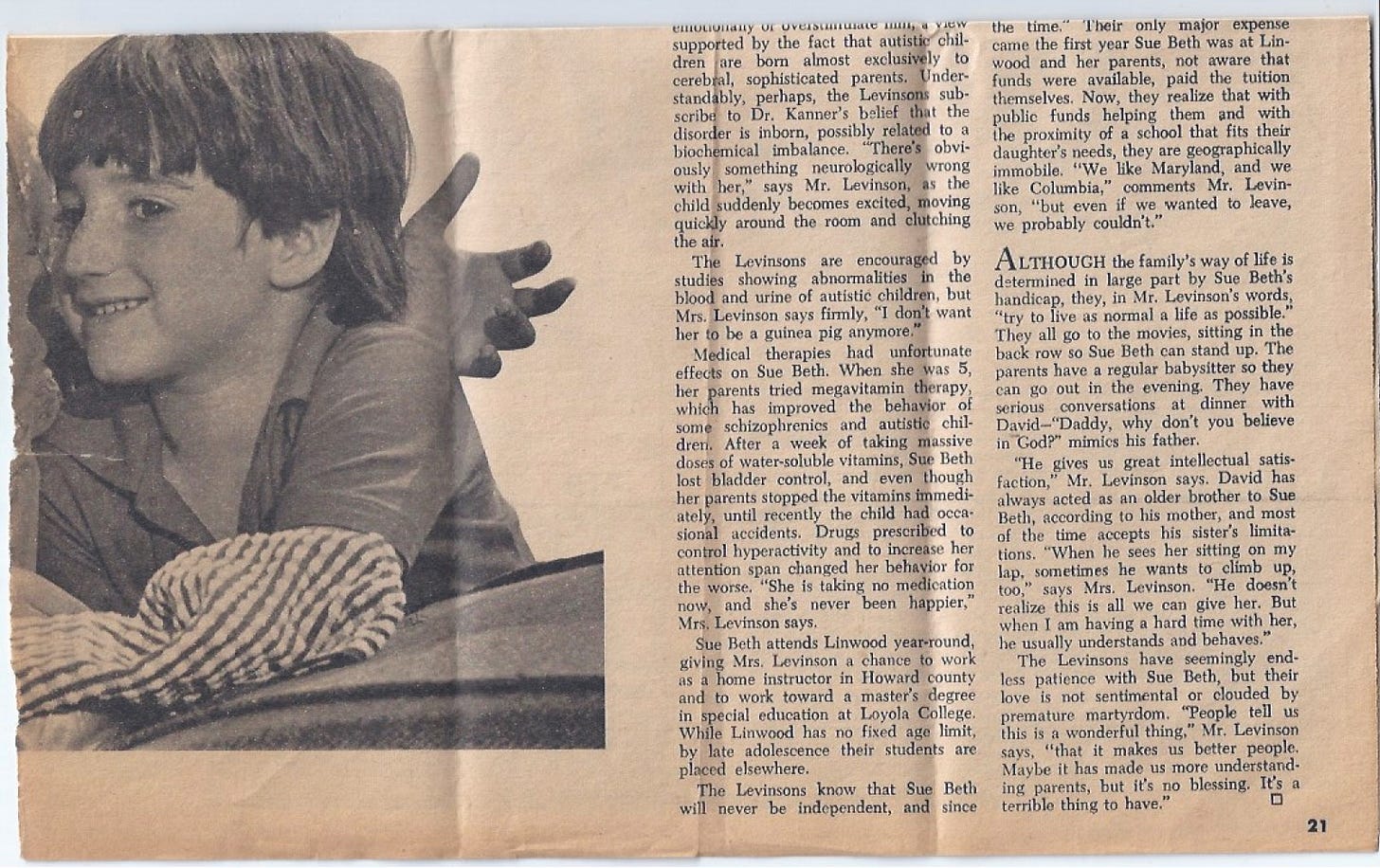

Sue Beth shares a moment with her brother David, Mrs. Lawrence Levinson says that in the last year her daughter has begun to give and receive attention for the first time. Sue Beth Levinson, 9, is autistic. But years of attention from her parents and teachers have had their effect. She can dress herself and ask for food in full sentences.

Shortly after the Levinsons moved to Baltimore from New York City, when Sue Beth was 8 months old, they began to think her development was not normal. She walked on her toes, looked past people instead of at them, had uncontrollable tantrums and did not respond to her name “I thought she was deaf,” says her mother, “but she would imitate commercials and sing songs. When she was 2 she could read brand names like 'Listerine' and 'Cremulslon’ but she couldn’t talk to us.”

They consulted their pediatrician, who told them what they needed was more children. At 2 1/2 Sue Beth went to nursery school, and after the first day the teacher confirmed their opinion that something was wrong.

She was taken then to Dr. Leo Kanner, the distinguished child psychiatrist, who diagnosed her as autistic. It was Dr. Kanner who first identified the syndrome in 1943, and the Levinsons consider themselves extremely fortunate that they saw him so early.

Within nine months—"we must have set a record,” says her father—Sue Beth was enrolled at Linwood Children’s Center in Ellicott City, one of the few private schools in the country for autistic children. Since then her progress has been "consistent but slow, like a very acute angle going up,” according to Mr. Levinson, a program validation officer at the Social Security Administration.

Sue Beth is larger than most 9-year-olds, and she still walks on her toes, which makes her seem even taller. When her mother tells her to "say hi” to a visitor, Sue Beth repeats “say hi" and, holding her mother’s hands, says her name.

“Do you want to go up and jump on the bed?” asks her father. He repeats the question a few times until she goes up the stairs of their spacious split-level home, leaving the others to talk. Included in the conversation is 6-year-old David, a self-possessed child who monitors the conversation eagerly.

You may have noticed we don’t have much furniture in the living room.” says Mr. Levinson. “We go through a lot of furniture.”

"It may seem strange that we encourage her to jump on the furniture,” joins in his wife, "but it releases a lot of tension in her.”

The few autistic children who learn to communicate tell of the terrible frustration of not being able to talk. While Sue Beth’s spontaneous speech is almost nil, her mother notes that in the past year she has become more content, giving and receiving affection for the first time and having fewer tantrums than ever.

“Tantrum” connotes a scene staged by a spoiled child, but the frenzy the Levinsons describe is much more distressing.

"We can never get used to it," says Mrs Levinson. "She has a weird wail, like a howl It’s like someone is torturing her."

When Sue Beth was younger, she had several tantrums a day. Any deviation in routine, even a detour from familiar roads, would cause uncontrollable panic. Now she simply clings to her mother or father when they go into a strange place.

Years of patient attention from her parents and teachers at Linwood have had their effect. Sue Beth can dress herself, ask for food in complete sentences when prompted and can recite her full name and address.

“She’s probably one of the few children who has never been lost.” says her father, but that is because one of the parents is always watching her. They had a close call when she was about 5 1/2. David, then a toddler, came crying to his parents and told them Sue Beth was leaving. They found her walking down the middle of the street, pulling her wagon. She still has no fear of cars, say her parents, nor understanding of what it means to be lost, but warnings and punishment mean nothing to her.

WHILE autistic children have limited ability to learn verbal and social skills, they often startle adults with their exceptional memories, mathematical facility and musical abilities. Sue Beth, her parents say, will occasionally do or say remarkable things-once, when she was 3, she built a tower of six blocks, a normal feat for that age. Her mother hasn’t seen her build a tower since. Her vocabulary has a wide range, but she uses only a few words regularly. These signs and her memory of songs she learned years ago lead her parents to believe that she may have normal intelligence somehow blocked from development.

One theory of autism blames “refrigerator parents" who isolate the child emotionally or overstimulate them, a view supported by the fact that autistic 'children rare born almost exclusively to cerebral, sophisticated parents. Understandably, perhaps, the Levinsons subscribe to Dr. Kanner’s belief that the disorder is inborn, possibly related to a biochemical imbalance. "There’s obviously something neurologically wrong with her,” says Mr. Levinson, as the child suddenly becomes excited, moving quickly around the room and clutching the air.

The Levinsons are encouraged by studies showing abnormalities in the blood and urine of autistic children, but Mrs. Levinson says firmly, "I don’t want her to be a guinea pig anymore.” Medical therapies had unfortunate effects on Sue Beth. When she was 5, her parents tried megavitamin therapy, which has improved the behavior of some schizophrenics and autistic children. After a week of taking massive doses of water-soluble vitamins, Sue Beth lost bladder control, and even though her parents stopped the vitamins immediately, until recently the child had occasional accidents. Drugs prescribed to control hyperactivity and to increase her attention span changed her behavior for the worse. "She is taking no medication now, and she’s never been happier,” Mrs. Levinson says.

Sue Beth attends Linwood year-round, giving Mrs. Levinson a chance to work as a home instructor in Howard County and to work toward a master’s degree in special education at Loyola College. While Linwood has no fixed age limit, by late adolescence their students are placed elsewhere.

The Levinsons know that Sue Beth will never be independent, and since victims of autism have a normal life expectancy, they accept the fact that she must live in an institution someday. "What bothers us,” Mr. Levinson says, "is that there aren’t a lot of facilities you would want to put your child in.” Along with other members of the Maryland Society for Autistic Children, of which Mr. Levinson is president, they are planning a small residential community for the mentally and physically handicapped. An architect is drawing plans for “Morning Star Village,” to be made up of small cottages with central workshops and recreational areas. Since health care professionals are recognizing the disadvantages of what Mr. Levinson calls "warehouses," they are hopeful that public and foundation funds will help to build the community.

The Levinsons admit that they are anxious about the future for a number of reasons. After six years at Linwood, Sue Beth still will not eat until she comes home at 3 P.M. Mrs. Levinson mentions that puberty is often upsetting to mentally handicapped women. And financial pressures, which have not been extraordinary until now, will multiply when Sue Beth needs residential care.

Through the "excess cost" program for multiply handicapped children, the state and county pay the $5,600 annual tuition at Linwood. "We were lucky we moved here,” says Mrs. Levinson, since we didn’t know Sue Beth was autistic at the time." Their only major expense came the first year Sue Beth was at Linwood and her parents, not aware that funds were available, paid the tuition themselves. Now, they realize that with public funds helping them and with the proximity of a school that fits their daughter’s needs, they are geographically immobile. “We like Maryland, and we like Columbia," comments Mr. Levinson, "but even if we wanted to leave, we probably couldn’t."

Although the family’s way of life is determined in large part by Sue Beth’s handicap, they, in Mr. Levinson’s words, "try to live as normal a life as possible.” They all go to the movies, sitting in the back row so Sue Beth can stand up. The parents have a regular babysitter so they can go out in the evening. They have serious conversations at dinner with David - “Daddy, why don’t you believe in God?” mimics his father.

"He gives us great intellectual satisfaction,” Mr. Levinson says. David has always acted as an older brother to Sue Beth, according to his mother, and most of the time accepts his sister’s limitations. "When he sees her sitting on my lap. Sometimes he wants to climb up, too,” says Mrs. Levinson. “He doesn’t realize this is all we can give her. But when I am having a hard time with her, he usually understands and behaves.”

The Levinsons have seemingly endless patience with Sue Beth, but their love is not sentimental or clouded by premature martyrdom. “People tell us this is a wonderful thing," Mr. Levinson says, “that it makes us better people.

Maybe it has made us more understanding parents, but it’s no blessing. It’s a terrible thing to have."

The definition of autism has broadened over the years to become a full-spectrum ranging from people who cannot independent function in society (like my sister, whose condition I will always think of as “real autism”, and who did not consent to this article, and would be incapable of consenting to this article) to people who have more independence and more social skills than my sister, but would be quickly identified as ‘different’ by anyone paying attention, to people who are merely fascinated by railroads and make highly valuable contributions to society, to people who are essentially indistinguishable from the neuro-typical (if such a thing even exists), and function well enough in society that they find, hold, and maintain jobs, mortgages, and their own families.

We are going in circles with autism diagnoses. I expect at some point in the future, as actual causes are found, autism will get redefined again, based not on symptoms but instead on its biological root causes or its treatments. Classifying based on symptoms is analogous to calling Dolphins as Fish because convergent evolution means they look similar. Conflating diagnoses of those who can function in society unassisted with those who cannot is medically unhelpful. Differentiating the diagnosis so that the appropriate responses are made (if any are available) one hopes will be a vast improvement for people like my sister.

If at some point in the future actual medical treatments become available, there will be choices and huge controversies which will make the current debates about gender identification look like play school.

Those who can understand the treatments and do not want to be treated, should not be.

Those who are incapable of consenting to or declining treatment will generally be treated, at their family’s insistence.

Young children will be treated who otherwise would have grown up to be productive members of society while being what we now in our more inclusive vocabulary term `neuro-diverse’.

After treatments become available, societal neuro-diversity will decline. We will have fewer neuro-diverse but socially accepted individuals in exchange for fewer neuro-diverse and dependent individuals.