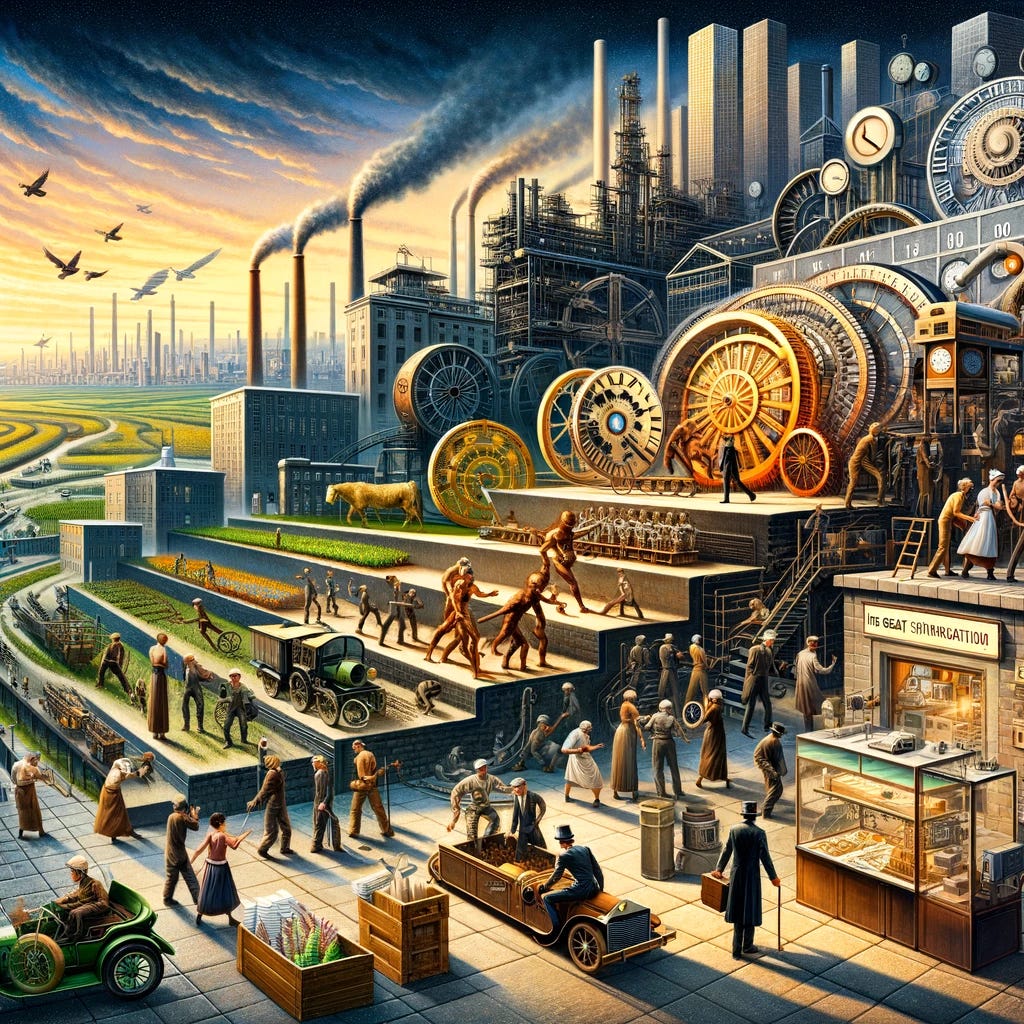

The Great Synchronisation and The Great Asynchronisation

Transiting the arc of history

"The Great Synchronisation" is a shorthand for describing the long historical process of increasingly precise coordination of time and activities. This began with the development of standardised calendars for agriculture. Mechanical clocks, often accompanied by town bells and factory whistles and which enabled the precise measurement, coordination, and communication of time. Schedules became a fundamental part of daily life, dictating work shifts, school hours, and transport timetables.

The Industrial Revolution furthered the need for synchronisation, with factories requiring workers to adhere to strict schedules to maintain efficiency, comporting the human, transformed effectively into a robot for the duration of the workday, to the assembly line, replacing the craftsmanship of the artisan, allowing an upscaling of total economic output at the cost of individual autonomy.

Urbanisation demanded the coordination of public services and transport to accommodate city dwellers, particularly the precisely scheduled factory workers, and schools to watch their children while the workers laboured. The concept of Just-in-Time delivery and production in manufacturing exemplifies this synchronisation, requiring precise coordination of material orders with production schedules not only within organisations, but between them.

The advent of the internet and digital technologies over the past three or so decades has ushered in "The Great Asynchronisation." The internet permits the transmission of information and communication across different time zones without the need for simultaneous presence. Asynchronous communication technologies such as email, forums, and social media enable people to interact without being online at the same time. The rise of remote work, especially with COVID, and globalisation further this trend, with employees working from different locations and at times that suit them best, and businesses operating across multiple time zones.

The transition from traditional to digital media is emblematic of this shift. Traditional media, such as TV, radio, and newspapers, relied on scheduled programming and fixed publication times. In contrast, digital media like streaming services, podcasts, and blogs offer on-demand access, allowing users to consume content at their convenience. This transition reflects long standing consumer preferences towards flexibility, personalisation, and interactivity that can now be served by newer modes of communication.

Asynchronisation of work (and shopping and other activities) may be better for mental health, and allow more people to participate more fully in society. It may also be better for productivity (if bad for the ego of managers). It is just terrible for many traditional synchronised services: mass transit, mass media, mass market, mass production, mass education, really mass anything.

Mass transit, like mass everything, requires scale, many people going from origin X to destination Y at time T. If we have a high enough frequency of service, and high enough demand, then coordination of T matters less, (and in fact, less peaking is probably an easier service to provide in many ways) though coordination across space remains important. But once people no longer travel to the same places in the same numbers, fixed route transit begins its slide down transit’s doom loop, the vicious cycle wherein service cutbacks reduce demand, lower demand reduces revenue, and lower revenue leads to further service cutbacks.

If this trend continues, and there is no reason to believe it won’t, it will be a struggle for urban transit to recover ridership from its pre-pandemic peak, much less grow, as it competes with more convenient, time and space untethered individual modes of transport (walk, bike/e-bike, car, taxi) that now have accelerated asynchronisation as winds in their metaphoric sails. To the extent that extant transit organisations do compete, it will be because they have become more like those modes (shared demand responsive transport), but that transformation is a costly endeavour, economically infeasible at scale in the absence of automation. And even if that market is to succeed, there is no guarantee the incumbent players will be the providers.

So the longstanding relative if not absolute “decline of transit”, a trend many countries have seen since the 1920s, with only occasional upswings, proceeds. Only in growing places with dense activity centres can transit thrive, and the minimum threshold of density for transit to be viable will continue to rise.

As we transit the great arc of history, exiting the "The Great Synchronisation" and entering "The Great Asynchronisation", we witness a societal shift from a world governed by strict schedules and centralised control to one characterised by flexibility, decentralisation, and personalisation. This transformation is driven by technological advances that have reshaped the way we organise time and space, work, interact, and consume, reflecting a broader trend towards a more asynchronous society.

Transit, especially rail transit, in most places is office-worker and CBD-oriented, the place most affected by WfH. Even in Sydney Australia, morning commute train use is at 70% of pre-pandemic. (Overall transit is 82% in Sydney, because buses and weekends are doing better). Melbourne is doing even worse (78% of pre-pandemic levels overall). Behaviour has shifted, transit is for obvious reasons slow to react. Bad urban planning doesn't help, but even the relatively good planning of Sydney or Melbourne cannot stop technological shifts.

'Asynchronisation' still has its limits: people normally sleep during the night, work during the day, and have to find the time to socialise with each other. Not everyone, but most people do all these things. Whether some people are involved in working globally across the time zones does not matter much for the local outcomes of it, as under normal circumstances socialisation would remain localised.

If the shift of a relatively limited number of workers to flexible and work-from-home arrangements puts a transit system into facing existential risk, it is not a problem of transit but how it is funded, how it is managed, how its purpose is defined and what is expected of it.

To me it looks like the discourse with regards to dying downtowns and the transit systems facing fiscal cliffs remains pretty much uniquely North American, and the reasons for that remain the same: (bad) urban planning.