Old People Shouldn't Drive

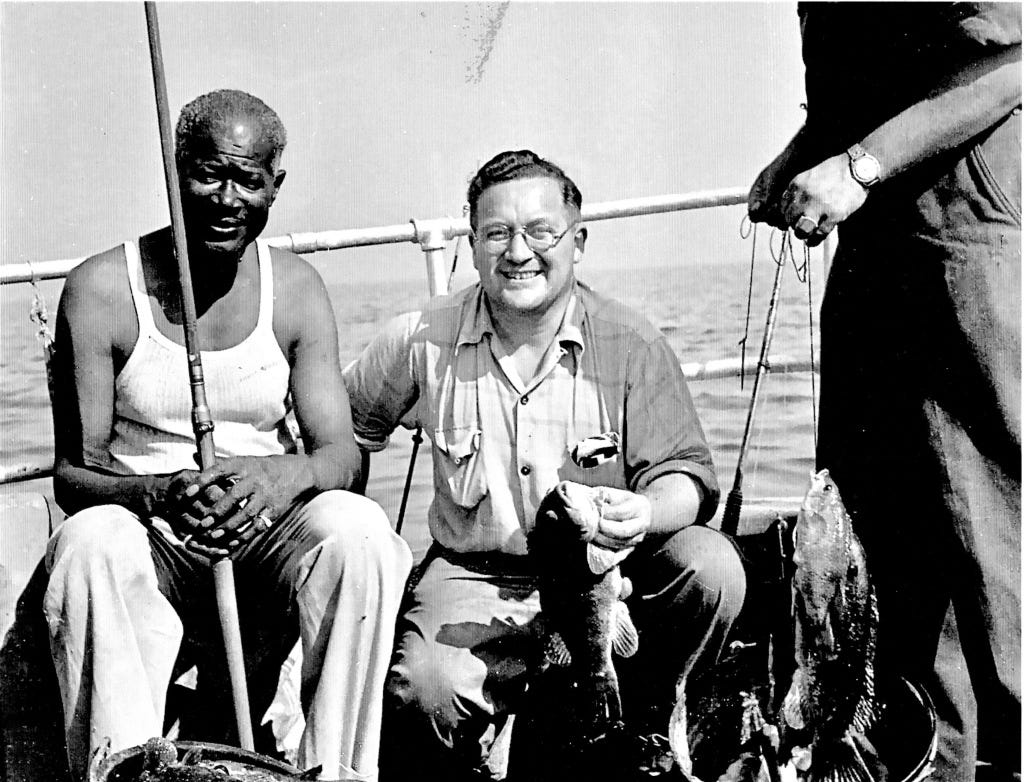

When my Grandpa Jack, who had worked for many years as a driver in New York City, moved to Florida, he naturally continued driving, sometimes longer trips, but generally shopping trips for my grandmother who never drove. Over time the amount of driving declined, and his eyesight worsened with macular degeneration. Eventually he only drove from his retirement community to the shopping centre across the street, one traffic light and about a mile away. As he joked, he stuck his cane out the window so that everyone would know he couldn’t see.

After he turned 88, my aunt was reasonably concerned about the risk he imposed to himself and others. She ensured he was sent a letter by the State of Florida Department of Motor Vehicles asking him to come in for a vision test, a test he knew he wouldn’t pass. He died soon thereafter. My aunt turned 88 this year. She still drives.

It seems fairly often that one hears news reports of an elderly driver colliding with someone on a footpath. This recent tragedy: Elderly driver, 91, hits three pedestrians at Melbourne playground is just one of many. Obviously not only older drivers hit pedestrians, but the effects of aging are a contributing factor that often get dismissed, while focus remains on speed and alcohol and drugs and youth and cell phones and so on, which also should not be dismissed.

RISK

There are two major risks to be concerned about

Crash risk to others

In the US the AAA Foundation found drivers 80+ more likely to be involved in crashes than middle-aged drivers per mile, though less likely than the youngest drivers (AAA Foundation). (Noting that seniors drive less, and so are often involved in fewer crashes per capita).Crash risk to themselves (fragility)

Aging bodies are less resilient. Vehicle occupants over 85 are up to 3× more likely to die in a crash than drivers under 20, and 20× more likely than drivers under 60 (Tefft 2008). The same crash that bruises a younger driver kills an older one.

WHY THEY STILL DRIVE

If the risks to themselves and others are so high, why do older people continue to drive? Aside from denial or simple lack of information, which one suspects is rare given the reminders that older drivers must receive when they go in for their eye exams:

Independence

Over 80% of adults 65+ hold licenses in countries like the U.S., and most drive weekly. Giving up the keys doubles the odds of being classified as socially isolated (OR = 2.1, p < .001) (Qin et al 2019). Driving is linked not just to mobility, but to mental health: the S.AGES cohort found it may act as a protective factor against depression (Baudouin et al 2025).Lack of alternatives

In most suburban and rural environments, transit is infrequent, walking is unsafe, and cycling impractical. Transport for NSW notes that driving cessation is strongly associated with depression and social isolation in the absence of alternatives (Transport for NSW). Globally, fewer than 10% of older adults regularly use public transport, and usually only when it’s abundant.Deconstruction of extended families

Though multigenerational living in the US was relatively rare by the early 2000s, recent years have seen a reversal. About 20% of older Americans now live in multigenerational homes, and between 2011 and 2021, the overall share of Americans in such living situations climbed from 7% to 26% (Pew 2022). Many of those multi-generational families though are parents and children, not necessarily grandparents and parents and children, thus not necessarily solving the isolation and transport problems.

THE REAL QUESTION

The issue is not simply whether old people should drive. It’s why they feel, like my grandfather in the 1990s, or my aunt today, they must. When mobility without a car is impractical or unsafe, driving becomes compulsory. Forcing people to quit driving under those conditions strips away not just transport, but autonomy, health, and social connection. Yet we have taxis available in a few minutes with the tap of a phone, and a call before that. Notably, for infrequent drivers this will be less expensive than the cost of vehicle ownership. Eventually AVs may be ubiquitous and solve the safety problem, but that’s a couple of decades away, as older drivers are least likely to be the technology’s early adopters.

WHAT TO DO

If we are serious about reducing risks while sustaining independence, the answer is systematic redesign:

Rigorous, functional ability tests, not age thresholds for licensing. (Recognising that ability changes over time, and can change suddenly, and we cannot, in practice, test continuously).

Housing near groceries, restaurants, healthcare, and other services, which doesn’t require a car. (Recognising we cannot move everyone, so this at best is a partial solution)

Accessible, frequent alternatives to driving (public transport, safe taxis and ridehailing, community shuttles, safe and smooth sidewalks with minimal tripping hazards, biking/triking lanes, and so on) designed for all ages—not just commuters. (Recognising we cannot afford (or choose not to afford) the public transport we have in many places.)

Safe street design with lower speeds and protected crossings, reducing fragility-related risks.

Of course, these are the things we should do for almost all problems with cars.

If “old people shouldn’t drive” is true, it is less an indictment of seniors than of the transport and land-use systems that make driving seem like the only viable option for people who grew up with automobility. A society that designs mobility only around the private car ensures that the moment you can’t drive is the moment your world collapses.