Transportist: Maintenance is an Accessibility Issue

Connecting the long and short runs

There is a dichotomy between the short and long runs. In planning we focus too much on the long run and large scale capital expenditures, and abstract-out issues like maintenance . (And in engineering, vice versa.)

Access is the ability to reach valued destinations. Maintenance ensures that systems keep running to their design specifications.

In the absence of maintenance, systems (or elements of systems) begin to fail, requiring repair or replacement, and in the meantime, closure. When system elements are closed, they can no longer be used to reach destinations, and thus, if they were valuable, access declines.

But with maintenance, those system elements also need to be closed to ensure they can operate in the future. So during maintenance, access is also temporarily reduced, people can reach fewer destinations in the same time, or take longer to reach the same destinations via a less convenient mode or path, or at a less desirable time.

So we want to minimise the costs of doing maintenance and the costs of maintenance to displaced users. This is typically formulated as an optimisation problem in the academic literature, though I suspect in practice it is pretty ad hoc, given the high number of variables and uncertainties associated with maintenance, so at best it is expert judgment.

That’s not unreasonable, but the experts are experts in construction, with some work in staging and project management, and are often not pricing customer delay directly.

I believe that with better coordination and advance planning: spatially, temporally, and sectorally, the same jobs could be conducted with less customer delay, and minimal additional costs.

Spatially: Work on an entire line at once, rather than section by section. If any link on a path is closed, the upstream and downstream links are effectively useless to them as well, so works on those links can be scheduled concurrently.

Temporally: Concurrent work as noted above, but also scheduling work during downtimes for service overnight. This is costlier to do, both because of labour costs, lighting costs, and the additional set up and breakdown of construction so that the line is operational the next morning, but especially for shorter and more localised tasks, this can minimise delay to users, who are fewer late in the evenings (and none if the line is not 24 hours in operation).

Sectorally: Ensure multiple tasks with different crews are simultaneous rather than in series. So people working on the track and on the overhead catenary and the signals can be coordinated to be in the same time window, rather than 3 sequential weekends. This requires coordination so people don’t get in each others’ ways. Obviously you want to avoid people getting electrocuted or run over. But with proper planning and communication, this can reduce system downtime.

These three dimensions work together to reduce system downtime and increase system accessibility more of the time.

Context

This idea arises in numerous contexts. Some examples below:

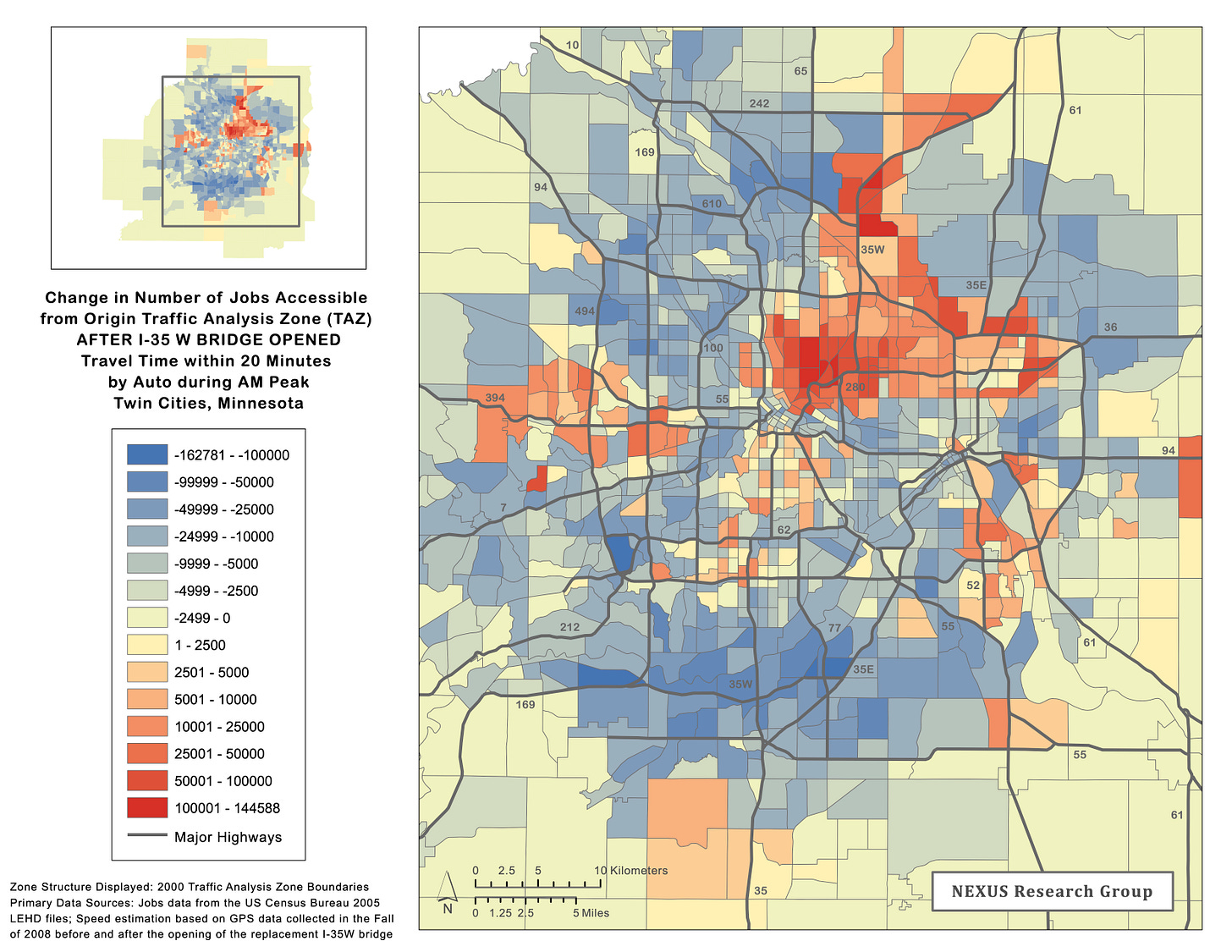

First, this was an issue with the 2007 I-35W Mississippi River Bridge Collapse (not quite lack of maintenance per se, but (a) a design mistake that was not caught (and probably could have been with the appropriate inspections) and (b) construction mistakes (loading construction materials on the bridge being repaired just above the design mistake). In any case, out of commission for a year, and the failure did spark a lot more maintenance, hopefully forestalling a repeat.

Next, the closure of the Bankstown rail line so it can be upgraded for Metro service, will take it off-line for 1-year. There will of course be replacement buses, but that is not the same thing. So will, say, 100 years of higher frequency and better quality of service, and additional capacity in the City for other lines, offset a year of no train service at all? It is a question, and though I think the answer is yes, it is not a slam dunk. In the meantime, access will be lost. [This recent announcement also rejects the speculation presented in the August Transportist that this project will be cancelled.]

Third, because of the maintenance push on Sydney Trains being made at the direction of new Transport Minister Jo Haylen, where weekend trackwork means less weekend transit access:

Buses replace trains: is Sydney doomed to endure the curse of weekend trackwork forever?. I got a nice interview in The Guardian on the subject, since the new government aims to reduce the maintenance backlog. I also got an interview on ABC Radio Sydney with James Valentine.

…

Prof David Levinson, a transport analyst at the University of Sydney’s civil engineering school, says he was struck by just how prominent train closures were after moving to Sydney.

“Other cities manage to make it work, do maintenance and keep trains running on weekends. It’s not like people don’t ride trains on weekends; in fact, weekend ridership is increasing lately.”

Levinson acknowledged the problem of night-time noise generating complaints, but pointed out that freight trains already run through Sydney at night. He says there should be a higher threshold for noise surrounding stations at night in the interests of keeping the city functioning.

“This is the price of living in a city, and being within walking distance of a train station. This is for the public good.”

“Train replacement buses in Sydney are so awful, and can get so loaded with people, it turns people off trains entirely,” he says. During peak times, train services in Sydney typically carry between 1,200 and 1,600 people, compared with about 80 to 110 on a bus.

…

Levinson says in China a “swarming” approach is used that floods tracks with workers and can achieve in a night what would take months in Sydney.

…